June 5, 2017 — The following was written by authors of a new paper on forage fish that found that previous research likely overestimated the impact of forage fishing. The piece addresses criticisms made by the Lenfest Forage Fish Task Force. The authors are Dr. Ray Hilborn, Dr. Ricardo O. Amoroso, Dr. Eugenia Bogazzi, Dr. Ana M. Parma, Dr. Cody Szuwalski, and Dr. Carl J. Walters:

First we note that the press releases and video related to our paper (Hilborn et al. 2017) were not products of the authors or their Universities or agencies. Some of the authors were interviewed for the video, and each of us must be prepared to defend what was said on the video. The LENFEST Task Force authors criticize our statement in the video that:

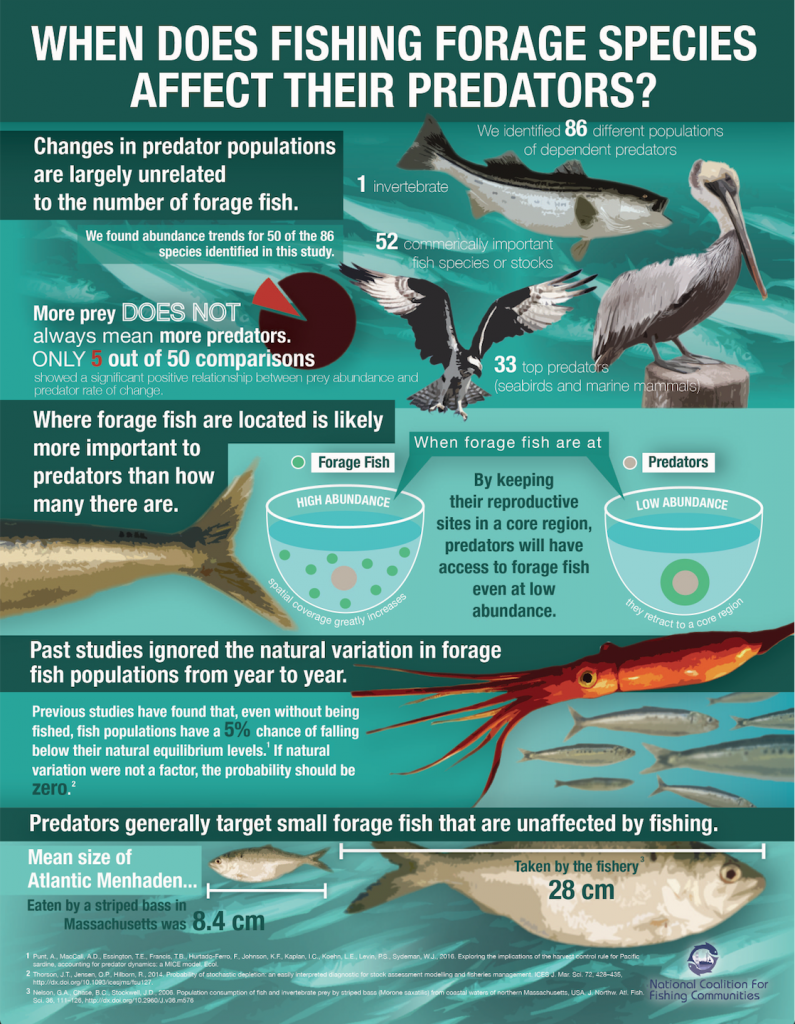

“What we found is there was essentially no relationship between how many forage fish there are in the ocean and how well predators do in terms of whether the populations increase or decrease.”

Our paper was specifically about U.S. forage fish, where we found very few relationships that were stronger than one might expect by chance. It is certainly likely that there are places where there is a significant relationship, but we noted that the LENFEST report did not include any analysis of the empirical data and relied only on models. Our point is that the models used by the LENFEST Task Force assume there will always be such a relationship, whereas in many, and perhaps most cases there may be little if any impact of fishing forage fish on the abundance of their predators. The scientific literature suggests that central place foragers, such as seabirds and pinnipeds at their breeding colonies, may be exceptions, and we acknowledge as much in our paper (p. 2 of corrected proofs, paragraph starting at the bottom of first column).

Specific response to the “shortcomings” of our study listed in the LENFEST Task Force response

- We included species not considered by the LENFEST Task Force to be “forage fish.” We simply looked for harvested fish and invertebrate populations that were an important part (> 20%) of the diet of the predators, and thus we would argue that our analysis is appropriate and relevant to the key question: “Does fishing the major prey species of marine predators affect their abundance?”

- The LENFEST Task Force authors criticize our use of estimates of abundance of forage fish provided by stock assessment models, and then suggest that because these models were not designed to identify correlations between predators and prey we were committing the same error that the LENFEST Task Force did, using models for a purpose they were not designed for. This is wrong: the stock assessment models are designed to estimate the abundance of fish stocks and the estimates of forage species we used to examine correlations with predators were considered the best available estimates at the time of the analysis. Similarly, the stock assessment models used for the predatory fish species represent the best available estimate of the abundance, and rate of change in abundance, of these predators. We did not claim the stock assessment models told us anything directly about the relationship between forage abundance and predator rates of change. We simply asked “Is there any empirical relationship between forage species abundance and either the abundance or rate of change in abundance of their predators?” The answer, with very few exceptions, was “no.”

- The LENFEST Task Force authors criticize our use of U.S. fisheries because they are better managed than the global average. Most of the key criticisms we made of the LENFEST study were unrelated to how fisheries are managed, but to the basic biological issues: recruitment variation, weak relationship between spawning biomass and recruitment, relative size of fish taken by predators and the fishery and the importance of local density of forage fish to predators rather than total abundance of the stock. U.S. fisheries are not only better managed, but also often better researched, so U.S. fisheries are a good place to start examining the biological assumptions of the models used by the LENFEST Task Force.

- We did not argue that fisheries management does not need to change – instead we argued that general rules such as the LENFEST Task Force’s recommendation to cut fishing mortality rates to half of the levels associated with maximum sustainable yield for “most forage fisheries now considered well managed” (LENFEST Summary of New Scientific Analysis) are not supported by sound science. Our analysis suggests that there’s little empirical evidence that such a policy will increase predatory fish abundance. Instead, every case needs to be examined individually and management decisions should weigh the costs (economic, social, and ecological) of restricting forage fisheries to levels below MSY against the predicted benefits, while accounting for uncertainty in both. Our abstract concludes “We suggest that any evaluation of harvest policies for forage fish needs to include these issues, and that models tailored for individual species and ecosystems are needed to guide fisheries management policy.”

- Essington and Plagányi feel we incorrectly characterized their paper. We simply rely on the words from the abstract of their paper. “We find that the depth and breadth with which predator species are represented are commonly insufficient for evaluating sensitivities of predator populations to forage fish depletion. We demonstrate that aggregating predator species into functional groups creates bias in foodweb metrics such as connectance.” Carl Walters, one of our co-authors and the person who conceived and built the EcoSim model certainly agrees that the models the LENFEST Task Force used were insufficient for the task they attempted.

Moving forward

We agree that the next steps are to move beyond U.S. fisheries and we are doing so. We have current projects doing a global analysis of relationships between forage fish abundance and the population dynamics of their predators. We have an almost complete review of recruitment patterns in forage fish stocks. We are doing specific case studies of other regions with models explicitly designed to evaluate the impact on predators of fishing forage fish. Finally, we are exploring alternative management strategies for forage fish, considering alternative recruitment patterns, across a range of case studies. We hope that many of the authors of the LENFEST report will collaborate with us in these efforts.