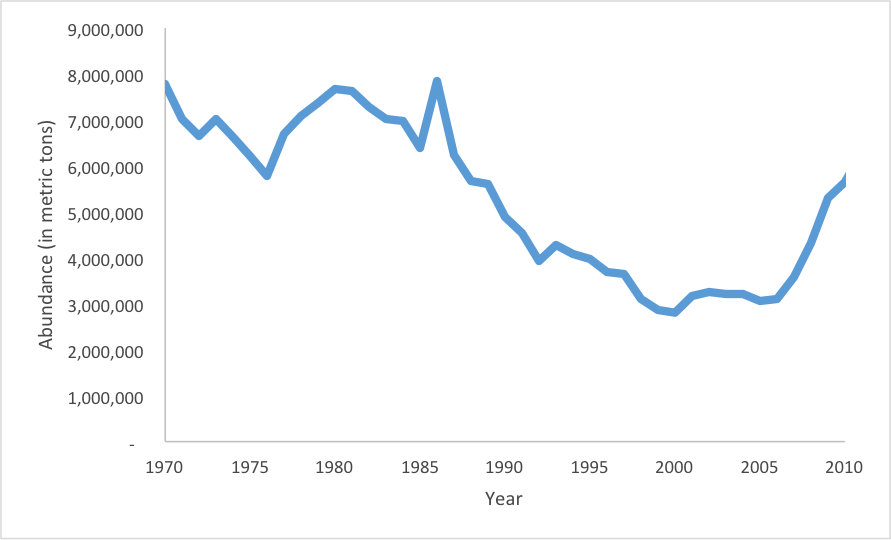

November 21, 2025 — Earlier this year, the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) doubled the total allowable catch (TAC) in the Northern cod fishery off Newfoundland and Labrador. This is the same fishery that infamously collapsed and was officially closed to all commercial fishing activity in 1992. The DFO’s decision has, unsurprisingly, been very controversial.

For this post, we spoke to several experts to understand the decision-making process that reopened this fishery and increased the TAC for the upcoming season. We learned that the assessment process has evolved during the moratorium, incorporating more ecosystem considerations, such as capelin, a major food source for Northern cod. Other environmental factors may have hindered cod’s recovery, however. Some stakeholders seriously challenge the appropriateness of the reference points used to assess the population. There is wide disagreement on what a successful Northern cod fishery should look like in 2025 and beyond.